Every metal marks a romantic chapter in human history.

...

As a result of their affinity for silver, lead deposits were eagerly sought in ancient times. The Greek mines at Laurium operating well before 3000 B.C. and the mines of the Iberian Peninsula beginning during the Iron Age are both celebrated for their contributions to the wealth of nations. Likewise, ancient Persian kings owed their legendary wealth to abundant lead/silver deposits. A breakthrough for extracting silver from lead ores, called cupellation, appeared around 3500 B.C. and greatly enhanced the popularity of silver. By the third millennium B.C., silver taken from lead ore had become the chief unit of exchange in the Near East, and the technology rapidly spread to other parts of the Old World. Cupellation remained the dominant process for silver recovery for nearly 5000 years, an important consideration in using archived lead in bogs and other deposits for paleoenvironmental detective work. By my estimate, annual production was about 160, 900, 11,000, 32,000, and 6000 metric tons during the Copper, Bronze, Iron, Roman, and Barbaric ages, respectively. Total production to 1000 A.D. is estimated at 32 million tons. Singer estimated that about 134 million tons of lead was discovered in the Old World throughout recorded history. Thus, about 24% of the discovered lead reserves were mined in ancient times, a more reasonable figure than previous higher rates.

Progress in lead. Logarithmic plot of historical lead production over time.

***

Another arena for massive growth was in the production of coinage Duncan-Jones reckoned that by the middle of the second century there were 7000 million HS of silver coins in circulation, which was roughly four times my estimate of the volume of Roman coins in circulation in the middle of the last century ВСЕ. And the volume of Roman coinage had already grown ten times in the century before that Perhaps. But confirmation of the huge volume of Roman silver-lead mining (silver was produced by cupellation as a by product of lead-mining) comes impressively from an apparently incontrovertible source

I refer of course to the Greenland Icecap, and the peat bogs or lake sediments of Sweden, Switzerland and Spain. A whole series of recent studies from a variety of sites have shown with remarkable concordance that the volume of wind-borne contaminants from smelting mineral ores reached a significant peak in the Roman period. Hong and associates showed that lead pollution from systematic samples of the Greenland icecap, datable to between 500 ВСЕ and 300 CE, reached densities four times the natural (i.e. prehistoric) levels. Renberget aL showed that lead contamination in a wide assortment of sediments from southern Swedish lakes reached a peak in or around the first century CE. Shotyk et aL showed from a study of a Swiss peat bog that there was a huge upsurge in lead pollution from the first century ВСЕ to the third century CE, when pollution (and presumably production) began to decline.

There seems little doubt among these investigators that the main source of contamination in this period was lead smelting and cupellation for silver and copper in the Roman empire, and particularly Spain. Hong and associates showed that copper production in the world rose sevenfold in the last five centuries ВСЕ, continued at a high but reducing level in the first five centuries CE and then fell sevenfold to reach a trough in the thirteenth century. Once again they are convinced that classical civilizations, and in particular the Roman empire was the major source of this wind-borne pollution.

Читать далее >>

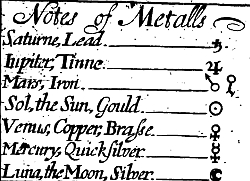

- into Sun and Moon. This use of planetary signs to designate metals dates from the infancy of alchemy. The Liber de mineralibus (III, i, 6; Borgnet ed., V), attributed to Albertus Magnus, gives the reasons for the planetary names of the metals. The Jammy (1651) and the Borgnet (1898) editions of the Alchimia frequently employ: Sol for gold, Luna for silver Venus for copper, Mercury for mercury, Saturn for lead, Jupiter for tin. When the planetary name is used in the Borgnet edition, the present translation capitalizes the name of the metal; for example, Venus is translated as Copper, but cuprum as copper. On the planetary designation of metals, see J. R. Partington, "Report of Discussion upon Chemical and Alchemical Symbolism, Ambix, I (1937), 61; and Pearl Kibre. "The Alkimia minor Ascribed to Albertus Magnus," Isis, XXXII (2) (June, 1949), 270. [Even more interesting than the replacement of the true names of the metals by those of the planets is the fact that the symbols representing the planets came to represent the metals, just as "we write H for an atom of hydrogen, [and] К for an atom of potassium,. . ."(F. Sherwood Taylor, The Alchemists [New York: Schuman, 1949]. p. 51). This convenient shorthand goes back to the earliest Greek alchemical manuscripts, dating from around A.D. 250. "We have considerable lists of the signs in the oldest Greek manuscripts. Some of them are derived from the signs of the planet with which the metals were associated, others from the pictorial representations of the things symbolized, others from the initial letters of the name.

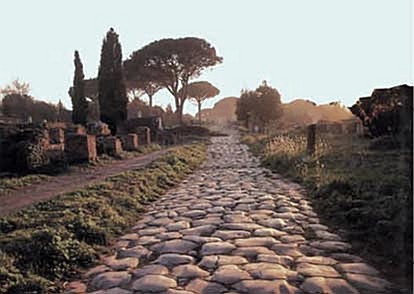

- into Sun and Moon. This use of planetary signs to designate metals dates from the infancy of alchemy. The Liber de mineralibus (III, i, 6; Borgnet ed., V), attributed to Albertus Magnus, gives the reasons for the planetary names of the metals. The Jammy (1651) and the Borgnet (1898) editions of the Alchimia frequently employ: Sol for gold, Luna for silver Venus for copper, Mercury for mercury, Saturn for lead, Jupiter for tin. When the planetary name is used in the Borgnet edition, the present translation capitalizes the name of the metal; for example, Venus is translated as Copper, but cuprum as copper. On the planetary designation of metals, see J. R. Partington, "Report of Discussion upon Chemical and Alchemical Symbolism, Ambix, I (1937), 61; and Pearl Kibre. "The Alkimia minor Ascribed to Albertus Magnus," Isis, XXXII (2) (June, 1949), 270. [Even more interesting than the replacement of the true names of the metals by those of the planets is the fact that the symbols representing the planets came to represent the metals, just as "we write H for an atom of hydrogen, [and] К for an atom of potassium,. . ."(F. Sherwood Taylor, The Alchemists [New York: Schuman, 1949]. p. 51). This convenient shorthand goes back to the earliest Greek alchemical manuscripts, dating from around A.D. 250. "We have considerable lists of the signs in the oldest Greek manuscripts. Some of them are derived from the signs of the planet with which the metals were associated, others from the pictorial representations of the things symbolized, others from the initial letters of the name. The world's first all-weather road system was built to facilitate modern warfare. Following their defeat in the Samnite Wars, particularly their humiliation at the Battle of the Caudine Forks along the rocky Apennines in 321 BC, the Roman military began to develop more effective attack formations and better transportation routes through uneven terrain. The formation, the legion, allowed troops to scatter when facing troublesome roads, then reunite easily when conditions improved. The improved transportation route was the Via Appia, or AppianWay.

The world's first all-weather road system was built to facilitate modern warfare. Following their defeat in the Samnite Wars, particularly their humiliation at the Battle of the Caudine Forks along the rocky Apennines in 321 BC, the Roman military began to develop more effective attack formations and better transportation routes through uneven terrain. The formation, the legion, allowed troops to scatter when facing troublesome roads, then reunite easily when conditions improved. The improved transportation route was the Via Appia, or AppianWay.

For a long time, the earliest aidence of wine manufacture came from Egypt from about 3000 B.C. Then, in 1991, Canadian graduate student Virginia Badler made a new claim about a dirty fragment of pottery from a Sumerian site in western lran dating from about 3500 B.C. The interior of the pottery, housed at the Royal Ontario Museum, was stained red. Some archaeologists thought it was paint; Badler thought it was wine.

For a long time, the earliest aidence of wine manufacture came from Egypt from about 3000 B.C. Then, in 1991, Canadian graduate student Virginia Badler made a new claim about a dirty fragment of pottery from a Sumerian site in western lran dating from about 3500 B.C. The interior of the pottery, housed at the Royal Ontario Museum, was stained red. Some archaeologists thought it was paint; Badler thought it was wine.

In the not too distant past

In the not too distant past